Shame: The Oft-Neglected Target in CBT for Social Anxiety

Shame: The Oft-Neglected Target in CBT for Social Anxiety

Written by Larry Cohen, LICSW, A-CBT

[This article is adapted from chapter 1 of

Overcoming Shame-Based Social Anxiety and Shyness: A CBT Workbook by this author.]

More Than a Phobia

Most self-help books about social anxiety disorder (SAD)—and some therapist manuals, as well—focus almost entirely on helping people overcome the severe impact that anxiety has had on their lives. This restricted approach is usually greatly beneficial. But, for the large majority of sufferers, social anxiety disorder, often called social phobia, is more than a simple phobia: an exaggerated and life-restricting fear. Unlike all other phobias, social anxiety disorder is usually based on shame-generating core beliefs about fundamental personal deficiency and perfectionistic self-expectations, which in turn lead to the exaggerated fear of judgment and rejection that is the hallmark of SAD. Shame is, for most people, a key ingredient in their social anxiety.

A phobia, of course, is an exaggerated fear or disgust about a type of situation, animal, or object that is so distressing that it makes it very difficult to pursue important life activities or goals. This is true of social anxiety disorder, too. Yet unlike all other phobias, SAD typically stems from distorted, negative, shame-based core beliefs about yourself and how you believe you are perceived by others: that you are deficient in some fundamental way(s) and are not good enough to be liked, respected, loved, or successful. Other phobias stem from distorted, negative beliefs about the feared situation, animal, or object.

In this way, social anxiety disorder is fundamentally different from all other phobias: negative core beliefs about yourself and the shame they induce are driving, causal factors of SAD for the vast majority of those who suffer from it. This is not true of other phobias.

Because of the fundamental role of shame in social anxiety disorder, strategies like traditional, habituation-oriented exposure therapy—the gold standard for treating other phobias—need to be adapted to also challenge and modify the core beliefs that cause so much shame, rumination and often depression. Outcome studies demonstrate that traditional exposure therapy is, indeed, quite effective in treating social anxiety disorder. But it is not as effective as when exposures are approached as behavioral experiments to test and challenge anxious thoughts, predictions and underlying beliefs about yourself, and how you are perceived by others.

Why is this true? One key reason is that anxiety habituates with exposure as you learn that your fears are greatly exaggerated, and that we can cope with them well. That is why exposure therapy is so effective for specific phobias. Unlike anxiety, shame does not habituate. You have to test and modify the beliefs that generate the shame in the first place in order to feel better about yourself and to gradually replace shame with self-confidence and pride.

Core Beliefs Generating Shame and Anxiety

Fundamental personal deficiency and perfectionist expectations about yourself are the most common themes of the core beliefs underlying social anxiety disorder. In addition, some SAD sufferers have core beliefs about the untrustworthiness of others. At their deepest level, many persons with SAD are troubled by absolute beliefs about self, about people in general, and about the way the world is or should be. Here are some examples of absolute core beliefs commonly underlying SAD:

— I’m socially inept and bad at meeting people.

— I’m fundamentally different and don’t fit in.

— I don’t measure up.

— I’m weird / not normal / not good enough.

— Others see me as weird and uninteresting.

— I should never offend or hurt anyone’s feelings, even unintentionally.

— People find me uninteresting / unattractive.

— Men / adults / attractive people can’t be trusted.

Also very important are conditional beliefs (often, but not always generated from absolute beliefs): if-then ideas about self, other people and the world. Common SAD examples of conditional beliefs include:

— If I make a social blunder, people will judge me harshly and reject me.

— If my anxiety or awkwardness shows, people will think I am weak or weird.

— If I displease or disagree with people, they’ll dislike me.

— In order to be accepted and liked, I must always meet others’ expectations of me.

— If people knew what I was really like, they would dislike me.

— If I get close or vulnerable to others, they’ll take advantage of me and hurt me.

It is not difficult to see how such core beliefs, be they absolute or conditional, generate both shame and anxiety, in addition to depression. In fact, the incidence of depression among persons with SAD is two to three times greater than that in the general public. For some SAD sufferers, their core beliefs are largely conditional, and so their shame and depression is largely generated by experiences in which they believe they have not met others’ expectations of them. For other SAD sufferers, their core beliefs are also absolute, often leading to chronic shame and depression.

SAD Facts

Social anxiety disorder exists when the fear of judgment (including criticism, rejection, scrutiny, and embarrassment) makes it extremely difficult to pursue one or more major life activities and goals, such as socializing, friendships, romantic relationships, advancing your career, speaking or otherwise performing in front of others, asserting yourself, using public bathrooms, being sexual, or even just being around others in a public place.

A momentary experience of social anxiety is completely normal, and in small measure, it is often helpful. It keeps you sensitive to the feelings and concerns of others and thereby allows relationships and society to function. (Only very arrogant or psychopathic people rarely experience momentary social anxiety, because the feelings of others have little value to them.) But the lives of people with SAD are debilitated by their repeated experiences of social anxiety, resulting in lessened social and recreational satisfaction; fewer friendships and romantic relationships; lessened likelihood of being married; less success in school and career; and/or a much greater likelihood of experiencing depression and alcohol use disorders.

Social anxiety disorder is the third or fourth most common mental health problem in the United States. Research shows that 12% of adults have experienced SAD during their lives; 7% have experienced it in the past year. The prevalence is even higher among adolescents, 9% of whom have suffered from SAD in the past year. Sadly, only 37% of people with social anxiety disorder recover naturally (without treatment) during their lifetimes. But the good news is that cognitive-behavioral therapy helps two thirds to three quarter of people overcome SAD.

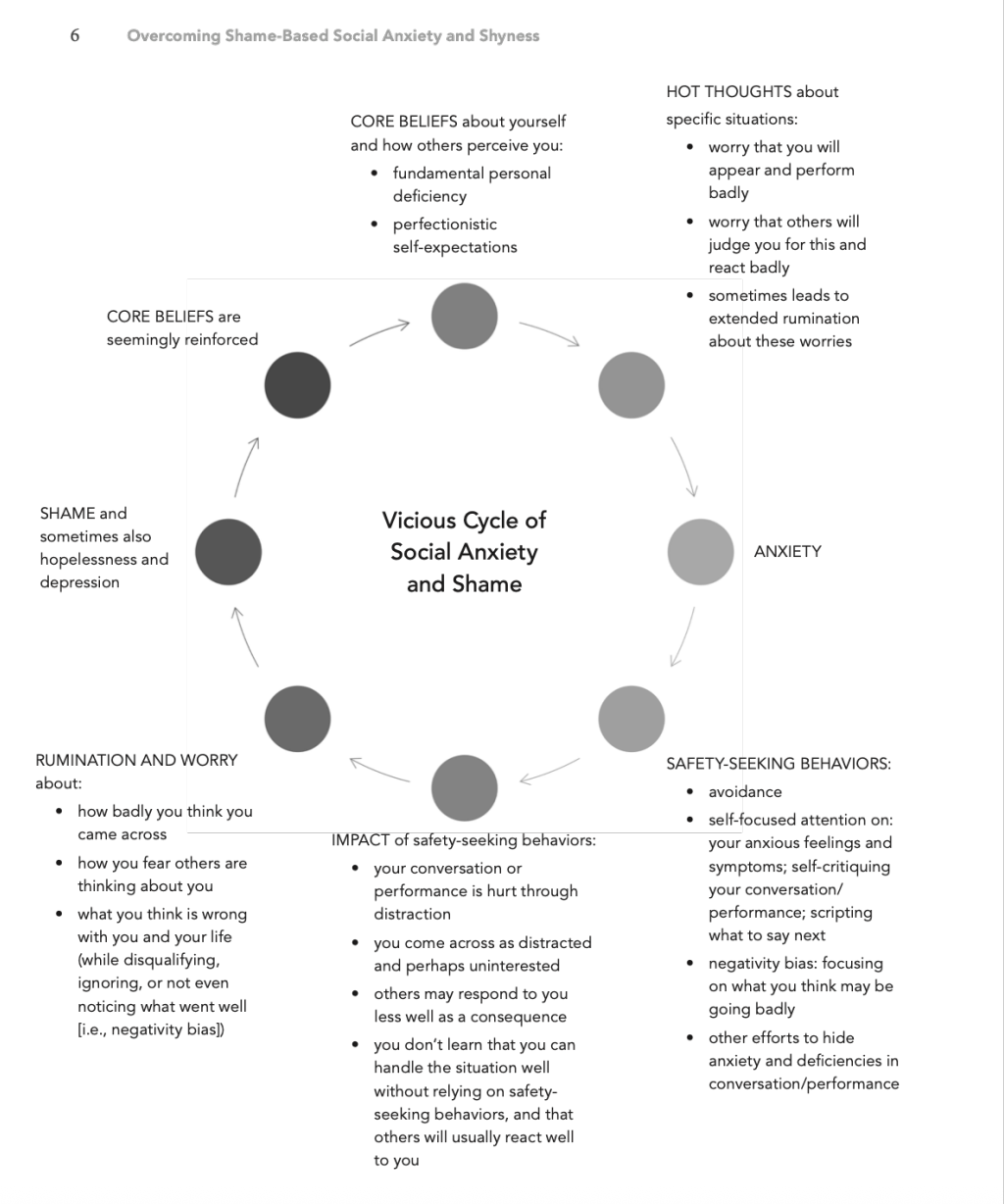

The Vicious Cycle of Social Anxiety and Shame

The experience of social anxiety involves a vicious cycle fueled by core beliefs of fundamental personal deficiency and perfectionistic self-expectations, and sometimes the untrustworthiness of others. These beliefs generate hot thoughts (automatic thoughts) about conversing or performing badly and appearing anxious or foolish in situations where you fear your deficiencies may be exposed. These thoughts generate much anxiety, leading you to rely on safety-seeking behaviors in an effort to avoid making a bad impression. Examples of safety-seeking behaviors include: avoidance; self-monitoring and self-critiquing performance and appearance; scripting what to say next; keeping attention off yourself; and trying to hide your anxiety. But these safety-seeking behaviors backfire and actually hurt how you come across, converse, or perform: an unintentional self-fulfilling prophesy. Because of your negativity bias (i.e., a safety-seeking behavior in which you mainly focus on what you think may be going badly during an interaction), you believe you made a much worse impression than you actually did, which leads you to engage in self-critical rumination and worry after the triggering situation and before the next one. This, in turn, causes you to feel shame and reinforces your core beliefs of personal deficiency and perfectionistic self-expectations.

This vicious cycle is illustrated in the following diagram:

Let’s take a close look at two common examples of social anxiety to see how this vicious cycle plays out. I commonly discuss one of these examples in the first or second session with a socially anxious client, using specific examples of the client’s own situational triggers, hot thoughts, core beliefs and safety-seeking behaviors.

Mingling with Strangers

Let’s say you’re invited to a party by a friendly coworker, Jason. You have a personal goal to make more friends, so you think that this party could be an opportunity to begin doing so. But you’re troubled by old core beliefs—seemingly supported by years of painful evidence—that you’re really bad at socializing and meeting new people; and if others see you appear anxious or screw up in the conversation, they’ll be turned off and think that you’re weird or uninteresting.

In the past, you’ve generally avoided social activities out of fear that your social deficiencies and anxiety would show, that others would react negatively to you, and that you would end up with feeling shame and depression. You’re very tempted to rely on your old safety-seeking behavior of avoidance this time, too. You spend a lot of time ruminating, worrying, and trying to figure out what to do. You consider telling Jason that you already have other plans that day. You think that Jason was just being nice in inviting you and doesn’t really care if you come.

You scold yourself with shame: “What’s the matter with me that I feel so anxious about going to a party?! Other people enjoy going to parties. Maybe this time will be different.” So you go.

After spending a lot of time worrying about what to wear, when to arrive, and whether you should come up with a last-minute excuse to not attend, you finally arrive at the party. With much anxiety, you quietly knock on the door and wait with mounting discomfort for what feels like a long time. You knock again, this time louder. Somebody answers the door, but it’s not someone you know. You manage to say that you’re here for Jason’s party, and that person lets you in but doesn’t introduce herself. You’re left standing just inside the door as you look around the large room and see that it’s crowded with people standing in small groups and actively chatting. You criticize yourself for not arriving earlier when there would have been fewer people. You’re trying to figure out what to do. You think about leaving, but you feel ashamed and criticize yourself for even thinking so.

You finally see Jason across the room, chatting and laughing away with people you don’t know. You can’t hear what they’re saying. You’re trying to decide what to do, but you’re troubled and frozen by anxious hot thoughts: “Should I go up to them and say hi, or would they think I’m intruding and being rude? Do others notice me standing alone so long, and are they thinking that I’m weird and unfriendly?” Then, to your surprise, Jason happens to turn a little. His eyes meet yours. He smiles and laughs. He turns back and continues laughing and chatting with his friends, who briefly glance your way, and then turn back.

You feel a surge of embarrassment. You have the hot thoughts that you’ve already made a terrible impression with Jason and his friends, who are probably saying negative things about you and even laughing at you. Your anxiety is increasing, and you’re thinking of just turning around and leaving, but feel too much shame for even considering that option. So you stay, take a deep breath, walk up to Jason, and timidly say hi to him and his friends.

They seem friendly enough. They try to make conversation with you, but you rely on your old safety-seeking behaviors of answering their questions in just a few words in order to get the attention off of yourself. You focus attention on your own anxious feelings and physical symptoms in a futile effort to control and hide them: your voice, which you think sounds horribly shaky with nervousness; your hands, which seem so jittery; and the warmth you feel in your face, which you imagine appears beet red. You also desperately try to script in your mind what to say next, and only come up with questions, again to keep the attention off of you. You criticize yourself for coming across so awkwardly. You end up just standing there quietly while Jason and his friends continue chatting, now ignoring you. Your safety-seeking behaviors backfire, making you appear uninterested and uninteresting to your conversational partners, who respond by saying very little to you. This fuels a self-fulfilling prophecy which you perceive as confirmation of your core beliefs about fundamental personal deficiency.

At some point you excuse yourself to go to the bathroom, where you spend time ruminating in self- criticism and feeling shame. After a prolonged escape in the bathroom—where you start feeling anxiety that others will think you’re weird for being there so long—you finally return to the party, grab a drink, and engage in other safety-seeking behaviors of standing off by the side, quickly averting eye contact with people, and looking at your phone a lot in order to appear busy. Again, these safety-seeking behaviors backfire and lead other to avoid you, thinking you’re unfriendly or uninterested.

The few times somebody does come up to try to talk to you, you rely on your other safety-seeking behaviors: speaking very briefly, focusing on your anxiety symptoms, and trying to script what to say next…all of which backfire, hurting the conversation and how the other persons perceives and responds to you. Each conversation is just as awkward and brief as the previous one. Your negativity bias kicks in, making you unaware that at least one person seemed to enjoy talking with you, and may even have been flirting with you. But by looking away and speaking only briefly, you came across as uninterested.

You finally sneak out of the party—too anxious and ashamed to say goodbye to anyone—and go home. There, off and on for weeks, you ruminate about how badly you think came across, feeling engulfed in shame about yourself and despair about your future. Your negativity bias keeps you stuck in self-criticism while disqualifying or ignoring the positive aspects of your attending the party. At work, you avoid or minimize interaction with Jason as much as possible out of fear of facing a negative reaction from him.

Speaking to a Group

Let’s say you’re at a meeting at work. Because you have the core belief that you’re fundamentally deficient at conversing in groups, and that others will judge you as weird and incompetent if they see you screw up or appear anxious in any way, you rely on the safety-seeking behavior of sitting silently and just listening to others speak in order to keep attention off yourself.

But then someone asks you a question and your anxiety surges. You now engage in the safety-seeking behavior of speaking very briefly, even though you have much more you could say, because you hate the attention, which you assume to be critical. You focus on your anxious symptoms in the hope that you can hide them from the examining eyes of others. When it’s your turn to present something, you focus on your notes or slides, reading them word for word rather than speaking freely, while avoiding looking at the audience. These safety-seeking behaviors backfire, hurting how you come across and what you say. Your negativity bias leads you to home in on someone who appears uninterested while not noticing others who look quite interested in what you’re saying. After the gathering, you ruminate in harsh self-criticism off and on for days, leaving you feeling deep shame, and setting yourself up to experience even more anxiety the next time you need to speak up in a group.

Breaking the Vicious Cycle

It doesn’t have to be this way! We can learn to break the vicious cycle and experience a positive, virtuous cycle instead. Imagine that you go to the party or speak at the group gathering with the core belief that you have strengths and weaknesses like everyone else, and that you don’t have to appear or perform perfectly for people to enjoy talking with you and be interested in what you have to say. Instead of relying on your safety-seeking behaviors, you focus your attention externally on what people are saying in the moment, and on expressing what pops into your mind naturally, without scripting. Instead of allowing negativity bias to lead to ruminating in self-criticism afterward, you pat yourself on your back for the positive things you did and the positive experiences you had during this interaction. You accept as completely normal that not every interaction will go ideally and that not everyone will like you, seeing that as just an indication that everyone has different preferences, not that you are deficient. Instead of feeling shame, you feel pride, self-confidence, and hopefulness for the future. Instead of worrying how the next interaction will go, you look forward to it as an opportunity for enjoyment and to move your life forward.

Integrative CBT

In addition to addressing both shame and and anxiety, my CBT for social anxiety workbook features an integrative CBT approach to SAD, bringing together the evidence-based strategies from all three “waves” of cognitive behavioral therapy. From first-wave (behaviorally focused) CBT, I emphasize exposure therapy while eliminating unhelpful safety-seeking behaviors and building confidence in your social skills. From second-wave (cognitively focused) CBT, I emphasize behavioral experiments designed to test and change anxious hot thoughts and underlying shame-based core beliefs, as well as strategies to reframe your thinking to lessen anxiety and avoidance, and to build confidence and pride. We also incorporate assertive defense of the self strategies to enhance confidence in your ability to handle fears come true with a sense of dignity, rather than shame. Second-wave CBT has been demonstrated to be the most effective treatment for social anxiety disorder. From third-wave (mindfulness-based) CBT — including acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT—I emphasize incorporating strategies to focus externally and with curiosity on the conversation, person and activity in the moment, and to defuse from your anxious thoughts and feelings while interacting.

Each of these strategies is discussed in depth, along with practice exercises and worksheets, in my recently published

Overcoming Shame-Based Social Anxiety and Shyness: A CBT Workbook. It is designed for socially anxious individuals to use on their own, with friends or in support groups; or to used together with a CBT provider during psychotherapy.

Resources

National Social Anxiety Center website: with troves of information, training and CBT-certified referrals for both clinicians, as well as socially anxious consumers.

Self-scoring questionnaires to assess social anxiety (adults and children), including questionnaires for shame, and for sexual anxiety.

Free training webinars on CBT for social anxiety.

Reference

Mayo-Wilson, E., S. Dias, I. Mavranezouli, K. Kew, D. Clark, A. Ades, and S. Pilling. 2014. “Psychological and Pharmacological Interventions for Social Anxiety Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis.” Lancet Psychiatry 1: 368–76.

About the Author

Larry Cohen, LICSW, A-CBT, is cofounder and Chair Emeritus of the National Social Anxiety Center (NSAC), an association of more than thirty regional clinics around the US dedicated to fostering evidence-based services to people struggling with social anxiety. He has directed the Social Anxiety Help clinic (NSAC District of Columbia) in Washington, DC, since 1990 where he has provided cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for more than 1,000 persons with social anxiety, and has conducted 100 20-week social anxiety CBT groups. Cohen is certified as a diplomate in CBT by the Academy of Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies (ACBT), which has also conferred on him the status of fellow for having “made sustained outstanding contributions to the field of cognitive therapy.”